I’m a westerner and I write about the West and its history, but I hope you’ll indulge me as I tell a family tale about how another region formed my life and my writing.

As a historian, I know that regional heritage isn’t just one, monolithic story. Even Hollywood knows this. In the movie Night at the Museum, Larry the night watchman tries to keep Union and Confederate soldiers in a Civil War exhibit from killing each other. He reminds them that the South lost the war, but still has some good things, like NASCAR and the Allman Brothers. That line is played for laughs, but Americans owe a debt to the South for other cultural contributions. Food comes to mind. And there’s another one that isn’t usually on a list of Southern specialties.

Aunts.

I’m a native Californian, second generation on my father’s side. But my mother was from Arkansas, which means that I grew up eating both sourdough bread and cornbread, and don’t ask me which one I like better because I can’t answer that question.

I can claim the South, but not just because that’s where my mother came from. My life was influenced, enriched, and molded, by my aunts, the kind of relatives who tend to show up in a Eudora Welty short story.

Mom was the youngest of the six Pickering kids, which included not only four other girls but also one, cherished brother. By the time my mother came along, the family was living in Bentonville, Arkansas, where they’d landed after generations in both southern and midwestern states. There, everyone grew up and some girls found husbands.

By World War II my grandfather had trouble finding work as a mason, and mom was the only child still at home. So, she and my grandparents moved to the San Francisco Bay Area for brighter opportunities. My parents met at San Francisco State University after the war and raised my sister and me north of the city in Marin County. By the time I was a pre-teen, all of the aunts and a clutch of cousins were living in California, and we wandered in and out of each other’s houses every year.

I learned early that if I sat quietly in a corner during family get-togethers, I would hear my aunts tell some great stories. These fueled my budding fascination with history, my early attempts at writing, and made me fall in love with language.

Verla and her twin sister Merla were the oldest. I only met Merla a few times, because she defected from the family for reasons that are still mysterious. The story I relish about her is from the time she and her husband lived in Louisiana. When heavy rains caused flooding around their house one summer, Merla sat on the porch with a .22 rifle shooting the water moccasins that were trying to swim through her front door.

Verla was also fearless. After graduating from Bentonville High School in 1931 she and a couple of friends drove west to Los Angeles, enduring numerous mechanical breakdowns and other adventures. I know this because Verla kept a diary about the trip. She wrote about the girls’ arrival in Los Angeles as sound, rather than sight: they knew they were close when they heard the bells of Aimee Semple McPherson’s Angelus Temple.

She later married a local man known as Mac, and they had a simple life together in Bentonville, though no children arrived. Then, at age forty, Verla announced that she was going to medical school in Little Rock and took off for the University of Arkansas. She was one of eight female students, surrounded on all sides by resentful men, and one of her classmates was future Surgeon General Joycelyn Elders, the first African-American to serve in that post. The women went out to dinner together regularly, but only at restaurants which would let Joycelyn in the door.

Verla became an anesthesiologist, and she and Mac moved to the Bay Area to be closer to other relatives. She kept all her gruesome medical books and had no objection when I wanted to look through them during our visits to their house. And she had a catch phrase about worthless people which I find useful in discussing some ex-boyfriends: “He wasn’t worth killing.”

Next in age was Barbara, known as Bobbie. All the other kids were rather tall, but Bobbie was petite, barely above five feet, even in heels. After she married Charlie they moved to California, and he began to raise quarter horses in the acreage behind their suburban home. Like her sisters, Bobbie always made sure everyone was well fed at her table, and she never met anything too humble to be slapped between slices of bread. As a girl she loved onion sandwiches, though she had to wait until a date brought her home before she could enjoy one. When I visited her family in the summers, I devoured mayonnaise and tomato sandwiches.

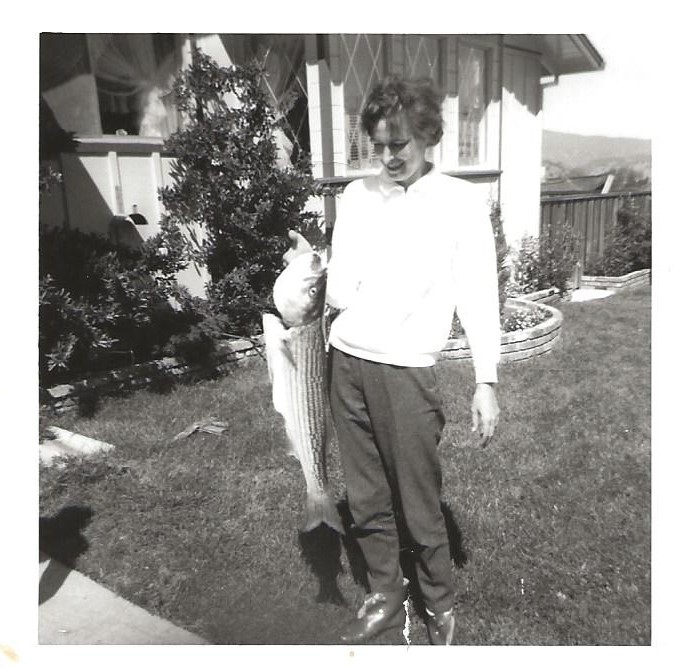

Bobbie

When barely into her seventies she was diagnosed with brain cancer, and I went to visit her a few days before she died. She was in her home hospital bed, in the twilight of consciousness that pain killers give, watched over by a nurse. I walked into the room and the nurse said, “Bobbie, look who’s here. It’s your niece.”

She turned her head toward me, opened her eyes, looked straight into mine and said, “Have you had your dinner?”

I assured her that I had.

Lois and her family lived the furthest away from us, in San Bernardino. But we saw her and our cousins frequently, both down there (a trip which always included Disneyland) and up north with the other sisters. Lois and I bonded early over our shared obsession with popular historical fiction, mostly about England, and whenever we were together, we gushed like teenagers over the latest offering by a favorite author.

She and her husband Orley were a ton of fun. In the summer of 1967, I took the bus south to visit the family. A bunch of us girl cousins sat up late every night eating ice cream, watching Johnny Carson, and the news reports about the gruesome death of Jayne Mansfield. Lois knew what we did and didn’t care.

Lois also loved words. One favorite phrase was, “Southerners are the only people who can pronounce the word egg with three syllables.” But her one-sentence summary about people from the past informs my own work to this day. “They didn’t know that shit stank.”

Brother J.R. lived in Minnesota with his family when I was growing up. I got to visit them in the summer of 1970, and it was then I realized that humor was not just a trait of the female Pickerings. I think I laughed the entire time I was in Minnetonka. We also took a road trip to Deadwood, South Dakota, where I got to gaze, mouth agape, at the graves of Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane. J.R. indulged his history-minded niece from California, and I will forever be grateful.

My mother, Evadne–known as Kelly to my dad’s relatives–was a beloved aunt to my many cousins. She also had lessons to give. For example, if I bumped up against a problem or obstacle she would say, “There is always an alternative.” Although she never learned to swim, and was pretty terrified of water, this didn’t keep her from jumping into the family fishing boat and handling a pole. The alternative to her fear was to wear a life jacket, a good pair of sneakers, and to keep her eye on my dad. She didn’t worry about my sister Jan and me — she made sure we learned to swim as early as possible. (I sat in the boat reading a book while everyone else was fishing.)

By the early 1990s only Verla and Bobbie were still alive. Both were also widows, and they decided to move in together to keep each other company, taking a house near where I lived. Verla was 76, Bobbie 68, and they decided they did not want to spend the time they had left just sitting around talking and smoking. All the sisters had started tracking down the family history when I was in junior high school, so Verla and Bobbie decided to get back to this research, but in a unique way. They turned their still-active minds to tales of another Southern staple: death.

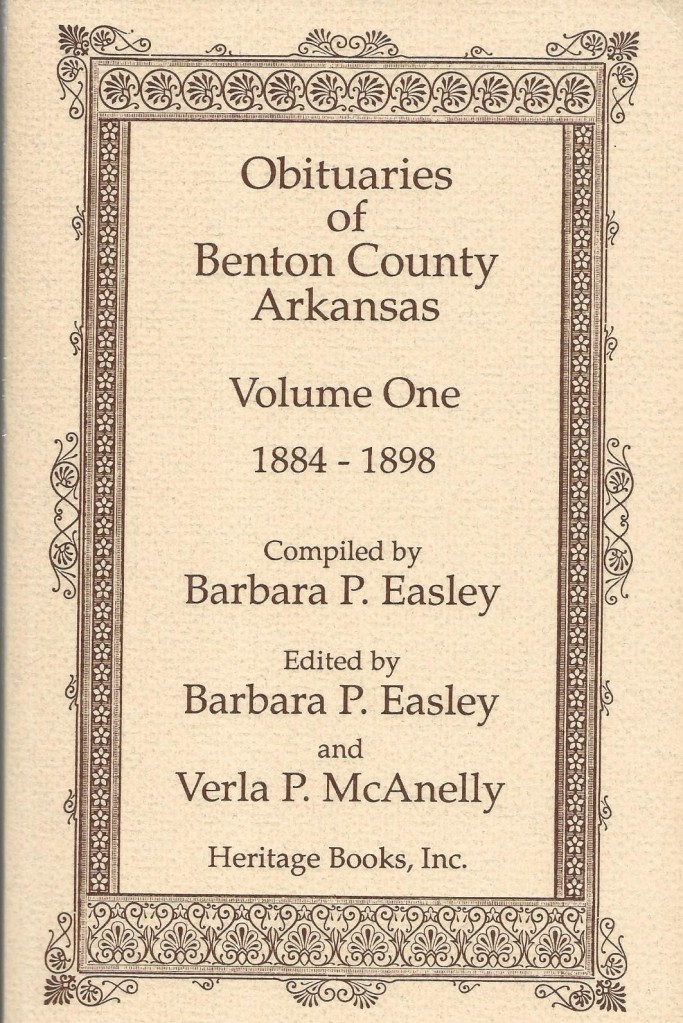

They bought microfiche machines and ordered microfiche copies of all the newspapers from Benton County, Arkansas. They spent hours every day reading and re-typing every obituary in every paper from 1884-1898. They organized the entries alphabetically by year and in 1994 published them in a book titled Obituaries of Benton County Arkansas, 1884-1898.

These obits are important historical records, a valuable research tool for genealogists, and every single one of them tells a compelling story, often with eerie modern echoes.

Here’s one from September 24, 1896. “Driven to savagery by his opponent in love and consequent over-indulgence in drink, Ben Bethel, two miles southeast of Exeter, Barry County, on Saturday night shot and mortally wounded Miss Maud Hayes and turning the revolver toward his own brain instantly killed himself.”

Sometimes the names are just as interesting as the obits. A few of my personal favorites are Mathias Splitlog, Theodosia Cowgur, and James Deatherage.

Written by gifted storytellers, these obituaries are either short and unfussy, or so long they are practically novellas. Verla and Bobbie knew that behind every name was a grieving family, and their descendants would be comforted when they found a familiar name.

They gave me a signed copy of the book on my birthday in 1994, writing “To Lynn Downey, from her loving aunts” on the flyleaf. They also went back to Bentonville to celebrate the book’s publication, and the folks at the Benton County Historical Society treated them like returning heroes.

But even as they enjoyed the acclaim, the aunts were plotting. There was no reason to stop at 1898, and over the next four years they published ten more compilations, from a wider selection of Arkansas newspapers, bringing the stories up to 1933. Each book’s cover had a vibrant, unique color.

They would have kept on going, but age and infirmity intruded. Bobbie’s brain cancer claimed her just as the final book came out. Verla developed macular degeneration and was no longer able to read. So, she shrugged and began listening to books on cassette tape, regularly upgrading her tape player. She died at age 97, the oldest aunt and the last surviving sibling.

I went to Bentonville for the first time on a business trip in 2013. I arrived a day early so I could wander the town, visit my relatives in the local cemetery, and try to find where the family home had been. I didn’t have the right information, so I dropped in at the Benton County Historical Society to see if they could help me. The director was at her desk, and while I waited for her to finish a phone call, I looked around at the bookcases. There they were: all eleven colorful copies of Obituaries of Benton County Arkansas, each standing out cheerfully among dull, reddish-brown books behind glass doors.

The director finished her call, and I asked if she could help me with some research. Then, pointing at the rainbow of volumes I said, “Oh, by the way, my aunts published those books.”

She stared at me for a moment and then her face lit up. She stood, came out from around her desk, shook my hand, said it was such a treat to meet me, and what brought me to Bentonville? I told her why I was in town, and that I wanted to see the house where the family had lived in the 1930s and 1940s, but I didn’t know where it was.

She sat back down again, picked up the phone, and said she knew someone at the bank who could help me. She punched in a number and after a few seconds, asked to speak to a woman whose name I can’t remember. She then said, “Listen, Verla and Bobbie’s niece is here and she’s looking for the old Pickering place. Drop what you’re doing, go into your title records, and get me the address. Call me back.”

A few minutes later the phone rang, the director made a note, and I had the address. It pays to be famous in a small town, even if it’s only through your aunts.

“Bereft” is a word you don’t hear that often anymore, but after Verla died I realized what it meant to be bereft of aunts. I’ve done what I can to keep them around, of course. I typed up a transcript of Verla’s travel diary. I have copies of the books that Lois and I loved. I eat Bobbie’s tomato sandwiches in the summer. And I have every volume of Obituaries of Benton County, Arkansas.

But nothing can replace the cadence of auntly voices, which always had the tang of their Arkansas roots. So, I remember and try to live by their example. I surround myself with words, and as a historian, I speak with and for the dead.

Thank you so much for that beautiful story! I learned things that I didn’t know, and remembered things that I had forgotten. I loved the pictures and the memories. I laughed and I cried, which is the mark of a truly good read!

LikeLike

Thank you, Darcy! I’m so glad you liked the story. xoxo

LikeLike

You and your family are amazing.

Sent from my Pihone

>

LikeLike

Thanks Mike!

LikeLike

It’s so much fun to travel across the country and find new threads that add immeasurably to the stories that fascinate us.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Lynn, the story is beautiful! I felt so grounded and “at home” reading it. What a beautiful picture you painted & shared of our family and their influences that shaped us into the strong women we are today. Many thanks and much love to you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Shannon, I’m so glad you liked the story. And thanks again for the great photo of your mom. xo

LikeLike

Wonderful story. I love your memories of your aunts. Bentonville has long been on my bucket list–to see Crystal Bridges and to see the town because it sounds charming in that southern, small-town way. Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike

Thanks, Judy! Crystal Bridges is an amazing museum, and Bentonville is definitely charming. I hope you can make it there soon.

LikeLike

Hi Lynn! This essay was amazing and such a treat to read. Having grown up in small-town Texas, your Arkansas roots are very familiar. And I loved the description of Merla shooting water moccasins to keep them out of the house. Whenever we water skied in Texas lakes, I couldn’t help but think I’d end up in a nest of water moccasins. Fun times?

LikeLike

Also, sourdough over cornbread any day! LOL

LikeLike

LOL! I still can’t choose one over the other…

LikeLike

Yikes, Cory! Water moccasins were never an issue in California lakes, but ooh whee. You’re braver than I am. Thanks for your comment, I’m so glad you liked the story.

LikeLike

What an enchanting story about your aunts and their various personalities and how they impacted your life.

LikeLike

Thank you, Eilene!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lynn, this is a lovely essay! When we get together, do remind me to tell you how I was lucky enough to meet Jocelyn Elders … 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks, Wynne. I want to hear that story!

LikeLike