Charlotte Blake at Elmira College, 1866.

As we start Women’s History Month, I want to tell you about someone I have long admired and written about: Dr. Charlotte Blake Brown.

In 1874 Dr. Brown and her family moved from Napa to San Francisco, where she hung out her shingle as one of the city’s few female physicians. Just twenty-eight years old, “Mrs. Dr. Brown” was an intelligent, cosmopolitan woman with deep New England roots, but life in the West shaped her childhood and her choices.

Her parents, Charles and Charlotte Blake, were natives of Maine, but their first three children were born in Philadelphia; Charlotte arrived in 1846. Charles Blake was an itchy-footed preacher and educator who had also studied medicine. He went out to California in 1849 to try gold mining and preaching and then brought his family West in 1851. They came via Panama, and five-year-old Charlotte vividly remembered native Panamanians carrying her on their shoulders as they navigated the Chagres River.

Charles and his wife ran a boys’ school in Benicia, across the bay from San Francisco, but following the deaths of two of their children, the Reverend took the remains of his family to Chile. After two years preaching to a small Protestant enclave, the Blakes sailed back to Pennsylvania in 1857.

As the Civil War began, Reverend Blake did a stint in Missouri with General John Frémont, fought with African-American troops, and served as a hospital chaplain in Chattanooga. His wife Charlotte also did some nursing. Meanwhile, daughter Charlotte entered Elmira College in New York in 1862 at the age of sixteen, where she met Olivia Langdon, Mark Twain’s future wife.

Chaplain Blake stayed in the Army after the war, and it then assigned him to Fort Whipple, outside of Prescott, the brand-new capital of Arizona Territory. In October of 1866 the Blakes stumbled out of the rickety wagon they had been traveling in for weeks and set their feet onto Prescott’s dusty streets. They had taken the Mojave Road from the California port of Wilmington, enduring punishing transportation and rude adobe overnight accommodations through army posts at Camp Cady (near Barstow, California), Marl Springs (one hundred miles further east in the Mojave National Preserve), and Hardyville (Bullhead City, Arizona).

They soon settled into life and routines. Blake had congregations at the fort and in town. Son Charles, a year older than his sister and a Yale graduate, started farming. And Charlotte opened a school for the handful of children who lived in town. An active, inquisitive mind like hers could not stay idle, but Charlotte soon gave up her school to take on something new: marriage and motherhood.

Like the Blakes, her husband Henry Adams Brown was from Maine, born there in 1842. Henry moved to Prescott sometime before 1866 and went into business with local merchant William T. Silverthorn, wholesaling hardware and dry goods. Henry and Charlotte met and made up their minds quickly to marry, and Reverend Blake performed the ceremony at Whipple on September 12, 1867.

Charlotte was soon pregnant with their first child, so they decided to move to Napa, California to be near Henry’s brother William and his wife. William was the postmaster in town, and Henry figured he could find a better paying job there. The Browns had a military escort out of Arizona Territory until it was safe enough for them to go on alone. One of the officers looked at the expectant Charlotte and said, “If we are attacked by Indians, the first bullet will be for you.”

Late 19th century Napa.

But they arrived safely in Napa in time for the birth of their daughter Adelaide in July, 1868. They had a son Philip in 1869 and Harriet came along in 1871. Henry was a bookkeeper for the Federal tax collector, a talent that would later make him a respected San Francisco banker.

What was Charlotte thinking about in her new home? The brainy, well-educated, ambitious twenty-five-year-old could not be content with simple domesticity. She decided to follow one of the family traditions and go into medicine: Charlotte was going to be a doctor. And despite expressions of horror from acquaintances and even her own grandmother, a pregnant woman who risked death in the Arizona desert would not let social convention stop her.

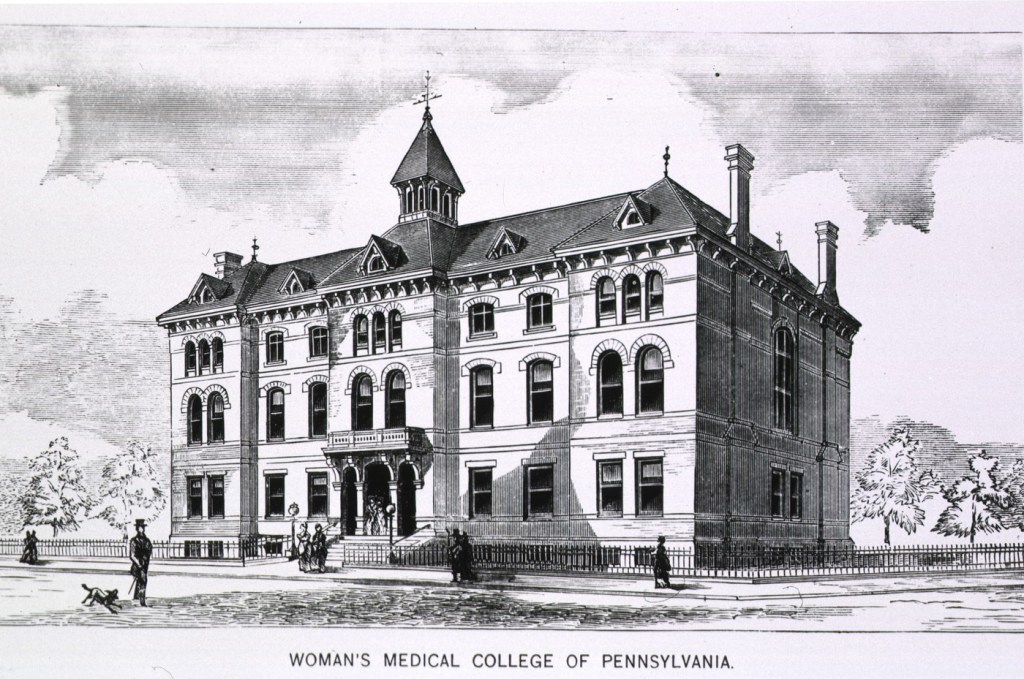

Besides, she was a veteran of multiple overland and ocean journeys, so spending a week on the transcontinental railroad held no terrors. She sped across country in 1872 to the prestigious Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in her home town of Philadelphia. Leaving her family behind was a tough decision, but her parents, now living in Napa, happily pitched in to help care for the little ones. Charlotte was away for two years and thrived at her studies, surrounded by equally intelligent and ambitious women.

With Charlotte gone, Henry Brown was left to share a home with his in-laws and three children. And we don’t know if Charlotte came home to visit during her time away. Does that make what happened on the afternoon of June 21, 1873 inevitable?

At noon that day Henry left his office to go home for lunch. As he walked down Coombs Street, tinsmith Ned Kimball began to follow him, holding a double-barreled shotgun in one hand. As Henry crossed the street Kimball stopped, raised the shotgun, aimed, and fired.

A volley of quail shot hit Henry in the back and hand. He yelped, reeled, and then ran toward his home a block away. Before he could get in the door, Kimball fired again but missed. Henry staggered into the house, Kimball put the gun over his shoulder, and walked calmly to the courthouse to turn himself in. Henry was covered with tiny pieces of quail shot, and though his life was never in danger, he was in a lot of pain. His father-in-law called a doctor who removed the pellets and treated Henry’s wounds.

And why did Kimball shoot Henry? Because he thought he’d been sleeping with his wife. Although the local papers said the affair was a rumor, it was easy to read the word “homewrecker” between the lines. And Kimball was apparently never charged or brought to trial for the shooting.

How Charlotte felt about her husband’s infidelities is unknown, but just weeks after she returned home from medical school in 1874, the family packed up and moved to a house near San Francisco’s Union Square.

Union Square, late 1870s.

It was the city where both Charlotte and Henry needed to be. Henry got a teller’s job at the Wells, Fargo & Co. bank, and Charlotte opened her medical practice. She was one of only a handful of female physicians and surgeons in the city that still flaunted its wild Gold Rush reputation. It was the perfect place to be a maverick.

Which is what Charlotte was.

She founded the Pacific Dispensary for Women and Children (today’s California Pacific Medical Center), performed surgeries never attempted in the West, opened the first nurses’ training school West of the Rockies, watched two of her children become doctors, treated the city’s Chinese residents when few others would, and visited other countries to expand her cultural and medical horizons. When she died in 1904, her funeral was attended by a new generation of female physicians that Charlotte herself had mentored and inspired.

She also inspired her children. Dr. Adelaide Brown made San Francisco’s milk supply safe in the years after the 1906 earthquake, just one of her many contributions to medicine. Harriet moved to Boston after her marriage and worked for women’s suffrage.

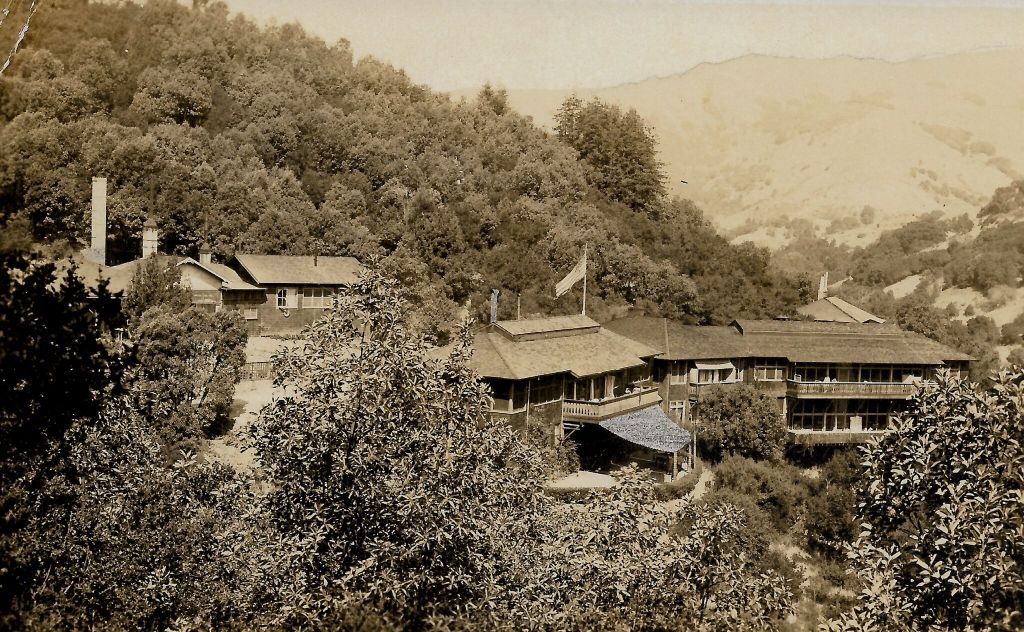

In 1911 Charlotte’s son, Dr. Philip King Brown, founded the Arequipa tuberculosis sanatorium north of San Francisco. It treated women exclusively, and in the 1920s one of them was my grandmother. Dr. Brown himself gave her a bed at Arequipa, and thanks to the care she received from him, and from his son, Dr. Cabot Brown, Grandma lived to be 102.

I also credit her long life to Dr. Charlotte Brown. From his childhood, Philip saw Charlotte’s deep commitment to women’s health. She went to work every day at her hospital, she was often called away from the dinner table to help a woman in labor, or tend to a sick child. He learned that women belonged in medicine, and that women deserved equal medical care with men. So, when he saw women’s TB rates spike after the 1906 earthquake and fire, he built a place to cure them.

Dr. Philip King Brown was Arequipa’s founder. But the seeds for its good work were planted the day his mother decided to become a doctor.

Opening image of Charlotte Blake: Courtesy Elmira College Archives, Gannett-Tripp Library, Elmira NY.

Very interesting article! And so many connections to other interesting stories too!

(But unfortunately for me, no connection to the Dr. Brown I wrote about a few years ago, who immigrated to California in 1849 and saved many from cholera).

LikeLike

I know, just a strange name coincidence.

LikeLike