I wrote the book Arequipa Sanatorium: Life in California’s Lung Resort for Women to tell the story of Dr. Philip King Brown, the pioneering San Francisco physician who founded the women’s tuberculosis sanatorium called Arequipa (and where my grandmother was treated and saved from death).

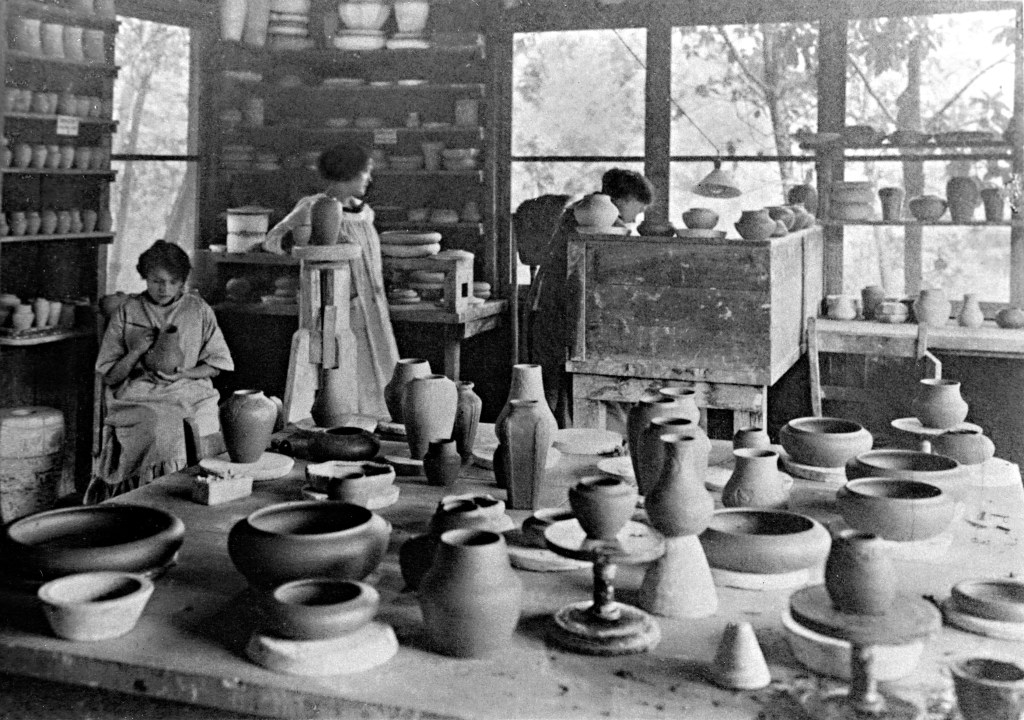

Along the way, I also learned about the innovative occupational therapy program Dr. Brown started up in 1912: making pottery. He believed in the link between art and healing, and so did his patients. For this Women’s History Month post, I want to tell you about one patient who stood out as a true artist at Arequipa and then made art her career.

Her name was Verena Ruegg.

She was born in San Francisco in 1895, and her father was the bookkeeper for the famed luxury good store known as Gump’s. When she was eighteen, Verena developed tuberculosis, and in July of 1913 she was admitted to Arequipa. She stayed at the sanatorium for nine months, and during that time she worked in the pottery studio (which was reserved for patients who were well on the road to recovery). Dr. Brown and the pottery director, famed ceramist Albert Solon, noticed that she had artistic ability far beyond that of the other women. She went home healthy in April of 1914.

About a year later, Dr. Brown got back in touch and made her an interesting offer. Arequipa had taken a booth at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, a huge world’s fair being held in San Francisco in 1915. Dr. Brown was setting up a pottery studio to show visitors how his patients benefited from his art therapy, and would she like to throw some clay again? She immediately said yes, and joined other former patients at the potter’s wheel who demonstrated how the bowls and vases were made. The women who were still at Arequipa made pieces to sell in the booth, and Verena worked at the PPIE for the duration of the fair.

After the PPIE closed, Verena traveled to Boston and spent time at the Arts and Crafts Society; she was listed as a “ceramic worker” in their April 1918 directory. By 1920 she was back in San Francisco and in 1921 she graduated from the nurses training school of Mt. Zion Hospital. Nursing may have been appealing after her experience at the Arequipa Sanatorium, but that’s not where her heart was.

By about 1924 she was living in Los Angeles, and a few years later she was working as a nurse at Good Samaritan Hospital. In 1926 she married an actors’ agent named Fred Robinson. Soon after she began studying at the Chouinard Art Institute and the Otis Art Institute, where she demonstrated her talent for illustration. In 1928 she won an Honorable Mention prize from the California Botanic Garden for her entry in their poster contest. (Verena is third from left in the photo below.)

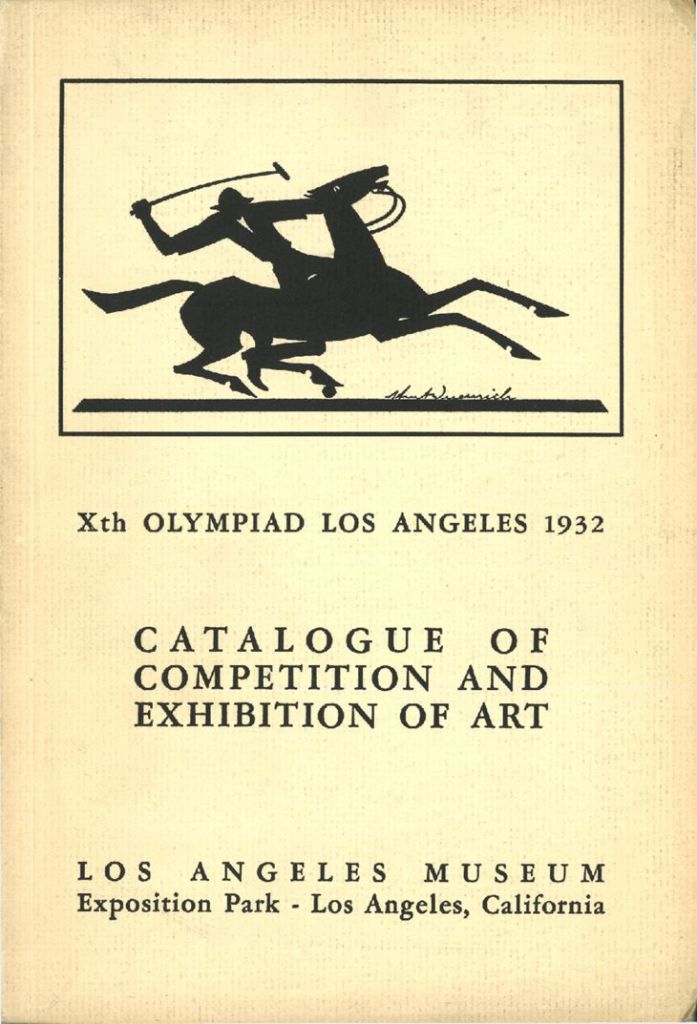

Fred Robinson supported her artistic career goals. She likely gave up nursing soon after her marriage to focus on her art, and by 1931 she was exhibiting her work at shows all around southern California, and under her maiden name.

(Yes, there was an art competition at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.)

She also exhibited and received prizes for her work at the Los Angeles County Fair from 1934-1941.

But 1939 was not a good year. First, the Robinson’s house burned down, though Fred managed to save many of Verena’s paintings. Then, on August 30, Fred was struck and killed by a speeding car while walking the family dog. Verena had to pull herself out of her grief, and find a good-paying job (she also sued the man who was driving the car).

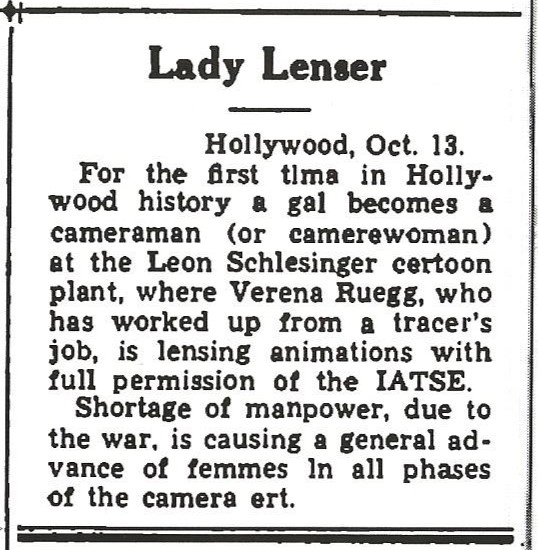

By March of 1940 she was working for the Disney Studios in the promotion department, though it didn’t take long for her talent to land her a chair in the Ink and Paint division. She traced the animators’ pencil drawings onto clear celluloid, called “cels.” She stayed at Disney until February of 1942 and then switched studios: she began to work as a tracer for Leon Schlesinger.

If you’re my age you recognize this name: he introduced the world to Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and all of the other Looney Tunes characters. Then, a few months into this job, Verena took the opportunity to learn something new and be the first woman to do it, which was reported in the October 14, 1942 edition of the Hollywood magazine Variety.

In other words, she probably wouldn’t have gotten the job if there wasn’t a war on. But luckily the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees supported her.

During the 1930s, Verena began to make sketches of dance performances, working with the troupes of famous choreographers like Agnes De Mille and Martha Graham. Dance illustration became the focus of Verena’s art for the rest of her life. She died in Los Angeles in 1973, and her papers and artwork are in Special Collections and Archives at the University of California, Irvine.

Did she always know she was an artist? Did her time at the pottery wheel at Arequipa in the years before World War I help her realize that she had such talent? Well, I’d like to think so.

What an amazing life well lived. Thanks, Lynn, for sharing Verna Ruegg’s story!

LikeLike

Thank you, Cory!

LikeLike

It’s good to see a really talented artist who in spite of numerous obstacles was recognized in her own time.

Now we need to bring art competition back to the Olympics. The ancient Greeks would have appreciated it as would many others who see sports in abstract terms.

LikeLike

That’s a great idea!

LikeLike

I really enjoyed and appreciated this book! Gre

LikeLike

Thank you, Joan!

LikeLike

wow!! 93The Silent Star in the Library

LikeLike