I’m reaching back into my Arequipa Sanatorium book again for the last Women’s History Month post, to bring you the story of a former patient that I had the great fortune to meet.

In the early spring of 2018 I was working on the manuscript for my book when I got an email from a doctor in Boston. He said he used to practice at George Washington University Hospital in D.C., and had a patient named Rose who was in her late eighties. She told him many stories about the years she spent at the Arequipa Sanatorium, and had kept in touch with this doctor even after he left D.C. He was intrigued enough to go on Google and find out more about the place. He also found me, because I’d been writing about Arequipa for years, and a lot of my work was online. We chatted over email and I told him I was writing a book.

Then he said, “Rose is still living in Washington. Would you like to talk to her?’

Well, yeah.

He got back to me a couple of days later with her phone number. I called her up, and thus began one of the most special relationships of my life.

Rose was now 92 years old. Going on 40. Our first conversation lasted two hours, as she unspooled her life story while I frantically took notes.

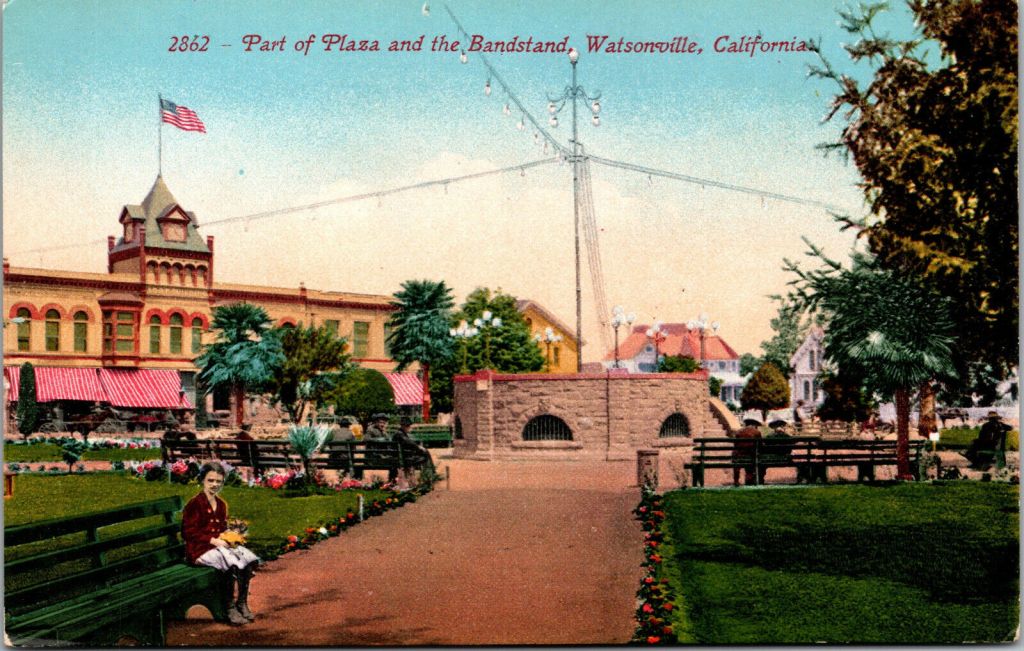

Born in San Francisco to a family who had emigrated from China before the 1882 Exclusion Act, Rose was the youngest of six children. Her grandfather owned an apple drying plant in Watsonville, an agricultural region south of the Bay Area, and her father was an itinerant worker in the fruit business all over California. When she was still a toddler, Rose’s family relocated to Watsonville, where she grew up going to the local public school and spending afternoons and Saturdays at the Chinese language school.

In 1940, Rose’s mother died of tuberculosis. Six months later, just before Rose’s fourteenth birthday, one of her teachers noticed that Rose has been sick a lot, and even when she came to class she didn’t seem well. The school arranged for her to see a doctor, who confirmed that she had TB in both lungs and had to leave school immediately. Bed rest at home would only go so far to getting her cured, but the doctor knew about the Arequipa Sanatorium. It was for women only, and a few years earlier had also started admitting young girls. After celebrating her birthday, Rose got into the family car with her brother and teacher, who drove her to to the sanatorium.

She was so ill that she didn’t get out of bed for years. Literally. She had to be carried to the bathroom and to the treatment rooms. It didn’t take long for Rose to endear herself to the doctors and staff members.

Dr. Cabot Brown. Courtesy the Brown family.

One of them was Dr. Cabot Brown, the son of Arequipa’s founder Dr. Philip King Brown. He and a visiting physician named Dr. Thomas Wiper vowed that they would keep Rose alive and give her a good life. She told me that they “…were rivals for my affection.” Dr. Brown called her Roses, and Dr. Wiper called her Rosie.

Other girls about Rose’s age were also getting treatment at the sanatorium, and one photo from her personal collection demonstrates how progressive Arequipa was. There was no racial discrimination in admissions. As my grandmother put it, “If you needed a bed, they gave you one.” Here’s Rose (second from right in the back row) with Asian, Hispanic, and Caucasian girls.

Most of the women and girls who were treated at Arequipa stayed for a few months or maybe a couple of years. Rose’s illness kept her there a lot longer. After four years of bed rest, she was moved to the ambulatory ward. The superintendent, Emma Applegren, loved Rose and was worried that she had not been able to enter high school. So Emma arranged for a local teacher to come out and give Rose enough lessons to catch up with her schooling.

Superintendent Emma Applegren

By early 1945, Rose was no longer contagious and was ready to go home. But she didn’t have a home to go to. Her family was scattered, her siblings married, and even at nineteen, she didn’t have the resources to support herself. So Dr. Brown and Dr. Wiper conspired again.

They gave her a small room at the sanatorium and gave her a job. She swept the floors, worked in the lab, and answered the phone. And she thrived. Dr. Brown was serving in the Pacific during World War II, but kept in touch with Wiper and with Rose, once writing to her, “I hear you’re running the place.”

A few months after her twenty-first birthday, Rose was discharged as cured. But she didn’t go far. Dr. Wiper was now running the California Sanatorium in Belmont, just south of San Francisco. He offered her a permanent job and a room in the nurse’s dormitory. She took the job and spent three years learning how to be back in the world again.

By the 1950s Rose was married and working in government service in Oakland and San Francisco. She had passed the Civil Service exam even though she hadn’t graduated from high school, but she got her GED anyway, knowing that it would help her advance. After her husband died she moved to Washington D.C. where she worked for the Small Business Administration and also spent time as a department store’s personal shopper for many of D.C.’s high powered women. One of them was Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. She also worked with the mother of famed Washington Post reporter Carl Bernstein.

After retirement Rose traveled and did volunteer work, but slowed down as she entered her eighties. She credited Dr. Cabot Brown and Dr. Thomas Wiper for her very life, and for teaching her how to stay healthy.

Fast forward to 2018. After my first conversation with Rose, she called me a few times a week, or I did the same. When I saw her name come up on my phone I smiled, because I knew I would hear her chirpy, “Helloooooooo!” She was invariably cheerful. Every time we chatted, she told me another tale from her years at Arequipa, and I was able to get her life story into my book.

Just before I learned about Rose, I got an email from Dr. Cabot Brown’s granddaughter Sarah, who was also looking for information on Arequipa and who happened to live in Washington D.C. We started up a lively email correspondence and I also met other Brown relatives who lived in the Bay Area.

In the summer of 2018 Sarah and her husband arranged for me to come to Washington to meet them, and to meet Rose.

I knocked on the door of Rose’s apartment, and there she was: her lipstick perfectly matched the pink of the flowers on her blouse and her smile matched her joyful personality. I also met one of her nieces, and we spent a few wonderful days together.

Rose, now in her nineties, needed help at home, where she lived alone. Sarah stepped up and helped Rose’s friends and caregivers. Sometimes she fell, and just brushed off what had happened. Nothing stopped her, nothing kept her from enjoying every day she had. But by December of 2020 her health had really begun to fail, and after going to a rehab center (the only time I ever heard her say anything grumpy) Rose passed away in January of 2021.

I’ve always said that Arequipa is a gift that I open again and again. One of the best gifts of all was meeting the brave, vibrant, funny, and ever-young Rose.

What a wonderful uplifting story!

LikeLike

Thanks! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful story about Rose, thanks so much for sharing it Lynn.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Another great one Lynn!

LikeLike

Thanks, Mike!

LikeLike

Now I, too, have a great affection for Rose!

LikeLike